Ballard Library and Neighborhood Center

Project Overview

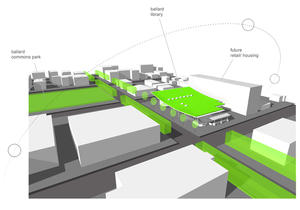

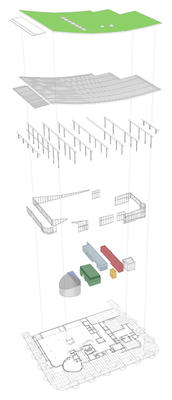

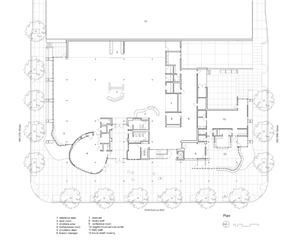

This project, the first major building designed within the new Ballard Municipal Master Plan Zone, consists of the 15,000 ft2 Ballard Library, a 3,600 ft2 neighborhood service center, and 18,000 ft2 of below-grade parking.

The new branch has self-checkout stations, 38 computers, a special area for teens, and a meeting room. The children's area in the building's prominent northwest corner overlooks the future municipal park space. Two study rooms provide space for tutoring and other activities, and a small conference room is available for meetings. A quiet room provides an alternative to the activity of the main reading room.

This project was chosen as an AIA Committee on the Environment Top Ten Green Project for 2006. It was submitted by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Additional project team members are listed on the "Process" screen.

Design & Innovation

Predesign

During the predesign phase the design team inquired about free daylighting services through the Seattle Lighting Lab. The modest public budget and state fee schedule did not allow for study models, so the Better Bricks Foundation offered a grant to assist with model building. An architecture student was hired to create a model specifically for the study, and a series of studies helped to identify the best options for obtaining even daylighting throughout the facility. Relites, overhangs, louvers, and the placement of openings and skylights were all tuned based on this information.

Early studies showed the importance of including adjacent buildings in order to help control the harsh western sun. The studies also indicated a potential heat-buildup problem in the southwest corner of the lobby. Several louver patterns were modeled in an attempt to balance solar gain and the transparency desired by the tenant.

The public nature of this building called for a public design process, despite the challenges associated with it. The collaborative effort included the architect, the Seattle Public Library, the Neighborhood Service Center, and representatives from various user groups. The community was represented by people who continually distributed information between their groups and the design team. This group effort allowed the voices of thousands of potential users to be heard.

Design

In the design phase the team identified a potential opportunity for using photovoltaic panels to produce electricity onsite. A series of inquiries led to a grant program through Seattle City Light’s Green Power Program and to a new product manufactured by Schott Solar in Germany. Understanding that eligibility for a grant would be predicated on educational opportunities, the team created a concept of a high-tech sun dial that would be clearly visible to the general public. The building's location and function lent themselves to the concept.

While Seattle City Light had provided traditional panels for educational opportunities, this was the first time they worked with the new photovoltaic film. A series of brainstorming sessions that included all parties led to an agreement in which the library was provided with both the photovoltaic film and photovoltaic panels for the roof. As the design was developed, meters were added to the sills of the wall to allow patrons to understand the relationship between the sun and the panels' orientation in the curved window wall.

Further design integration led to the addition of subtle details, such as separating the solar panels and providing clear glass behind the signage band, allowing it to be backlit by the lobby's interior lighting.

Artists were selected prior to the commencement of schematic design to allow public art to be integrated into the overall building design.

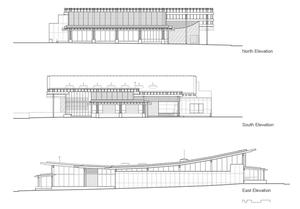

The Ballard Library and Neighborhood Service Center draws on this Seattle neighborhood's Scandinavian and maritime roots while focusing on the future of the community, composed of a young, diverse population.

The building presents a powerful civic face along a pedestrian corridor. The main entry is pulled back from the street, allowing for a deep front porch that joins the library and the service center under a large canopy. Grouped site furnishings encourage human interaction, reinforcing the civic nature of this sheltered space.

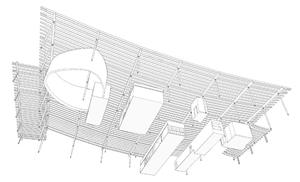

The gently curving green roof absorbs water, reducing stormwater runoff. The periscope and observation deck invite visitors to engage in the roof's ecology above the street. Daylighting studies allowed the team to maximize the use of varying intensities of natural light, and metered, photovoltaic glass panels shade the Neighborhood Service Center lobby, demonstrating the effectiveness of photovoltaic technology in the Pacific Northwest.

The design team hoped to create a facility that would be a dynamic teaching tool for green design and environmental awareness. The project illustrates that green building is feasible within a modest budget and presents an ideal example of some of the benefits that can be realized when green design combines with extraordinary architecture.

Regional/Community Design

Ballard is evolving from an old Scandinavian outpost to one of Seattle’s most popular neighborhoods. The district is rapidly becoming the civic core of the neighborhood, easily accessible by foot, bicycle, or public transit, including several bus lines. A pedestrian zoning overlay was recently adopted to promote development of this nature.

The Ballard neighborhood is deeply rooted in Scandinavian tradition and culture, and the nearby working waterfront lends a strong maritime tradition. The design of the building was intended to reflect these cultural roots while, at the same time, providing a new focal point for the developing neighborhood. The building's large, covered "front porch" serves as a civic plaza and provides opportunities for casual gatherings or for larger community gatherings.

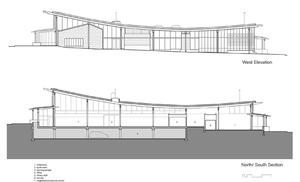

The site is located on a city block with the longest public face facing west. A public plaza, covered by a curving green roof, is located along the western, entry face of the building. The west face is located on a developing pedestrian core within the Ballard Municipal Master Plan. The site is located one block from the main marketing street in Ballard, and diagonally across the street from a new public park. The large west porch, covered by the green roof, affords protection from the wind, rain, and sun. The building’s covered porch, generous landscape, street trees, and large green roof provide an oasis in all seasons along with a comfortable microclimate amidst all of the impervious surfaces typical of an urban environment.

Encouraging and educating users about the availability and importance of alternative transportation was an early project goal. The site's location is ideal for its proximity to bus routes, a new park, and businesses; the neighborhood has a strong pedestrian nature. Ample bicycle racks are located on the property, including in the covered parking garage. The building's lobby has readily accessible information outlining alternative means of transportation to and from the area. Additionally, the library offers financial incentives to employees who travel using alternative modes of transport. Only 0.29 parking spaces are provided per occupant, and 73% use alternative transport options.

Land Use & Site Ecology

The site, located in an urban context, was redeveloped for this project. The challenge was to develop the site in a restorative manner. Formerly home to a bank and a parking lot, the entire site was covered by hardscape. Today, due in part to the green roof and planters at the building perimeter, hardscape covers only 20% of the lot; 80% is vegetated.

The rooftop is planted with is a mix of self-sustaining, drought-tolerant, indigenous grasses and sedums planted in a pattern that mimics a windborne casting of seeds. The green roof limits and filters runoff, and the water retained in the roof assembly irrigates the roof plantings. The green roof also provides habitat for bird life and diminishes the building's contribution to the urban heat-island effect. The relatively low height of the building will provide green views from neighboring urban properties as they develop to allowable heights.

Bioclimatic Design

Visual Comfort and The Building Envelope

-Use large exterior windows and high ceilings to increase daylighting

Visual Comfort and Interior Design

-Design open floor plans to allow exterior daylight to penetrate to the interior

Visual Comfort and Light Sources

-Provide illumination sensors

Light & Air

The building was designed to bring natural daylight deep into the building, minimizing the need for electric lighting during daylight hours. Photosensors ensure that electric lights are dimmed or turned off when daylight is sufficient.

Water Cycle

Native vegetation covers 5,071 ft2 of the site. The green roof covers an additional 18,100 ft2 of contiguous roof surface. Faceted planes of the curved roof create six microclimate conditions, each a separate exposure with differing water retention properties based on slope and orientation. The upper edges slope more steeply, retaining less water but offering the highest opportunity for evapotranspiration. The lower slopes retain more water and are more protected from prevailing breezes. Plant species were selected based on the specific conditions and located as they might be through natural propagation. Monitoring the species will show which plants survive best in specific conditions. Irrigation needs were minimized by the selection of drought-tolerant species.

Local interest groups are collaborating to install water-monitoring devices on the green roof. Data collection will be valuable in assessing the performance of the green roof over the life of the structure.

Outdoor water use is limited a computer-controlled irrigation system, and indoor water use is limited through low-flow fixtures, faucets controlled by sensors and timers, and waterless urinals.

Energy Flows & Energy Future

The Library and Neighborhood Service Center are two separate entities with different energy and conditioning needs. Mechanical units serving the two uses individually were isolated and located to simplify and reduce the length of duct runs. Simplified layouts reduce the amount of energy required to move air and reduce the loss of energy between the source and the use point.

Taking care to reduce heat sinks (common in concrete construction) led to innovations in the structure of the building. Precast concrete planks, supported by cast-in-place concrete columns and beams, are covered by rigid insulation and a floating slab. Conditioned interior space is completely isolated from the garage below. Data and electrical runs are located in the floating slab, allowing for flexibility in the future.

The design team worked with the Seattle City Light's Green Power Program to install rooftop solar panels, and, in the curtainwall, glazing with photovoltaic film. The photovoltaic glazing is one of the first such installations in the nation. The power generated by both systems is fed back into the power grid, and Seattle City Light continues to monitor the performance. The photovoltaic glazing also shades the lobby of the Neighborhood Service Center, eliminating the need for other shading devices, and minimizing the need for mechanical cooling. Meters at the base of these windows allow patrons to study the path of the sun and its effects on individual panes of glass in the curved wall of photovoltaics; In this way, the building features a high-tech sundial.

Energy-efficient light fixtures were used throughout the project. Photocells and occupancy sensors ensure that electric lighting is not used when it's not needed.

Materials & Construction

The project team was committed to incorporating products with recycled content. These included recycled-glass backfill, concrete forms made from milk cartons, and artwork made from heated sheets of post-consumer plexiglass originally manufactured from recycled milk cartons.

Many components were manufactured by the source suppliers, limiting field-fabrication and assembly time and simplifying the recycling of fabrication waste. Using simple, durable materials eliminated the need for the layers of finishes typically used in public construction.

Similar environmental goals were used in designing furniture for the building. A design based on nested panels allowed for the maximum use of 4x8' sheets of plywood, and assembly utilized a series of slots and tabs requiring no fasteners. The furniture shipped flat, maximizing the amount of furniture shipped per load. The architect designed site furnishings using recycled-content steel sheets bent to form simple, sculptural seats and waste receptacles. The design reduced both the energy use and the cost of fabrication.

Long Life, Loose Fit

Major building components, selected for durability, are also recyclable or reusable. The glulam roof structure was erected with bolted connections, allowing for easy disassembly. Connectors and timbers could easily be salvaged for future use. The aluminum curtainwall is stick framed, and much of it could be reconfigured for reuse in smaller projects. The wood and galvanized metal siding was fastened with screws, allowing for disassembly and reuse. The concrete could be crushed and used for site walls or paving surfaces.

The eastern wall of the parking garage was structured to allow for the removal of two panels to accommodate expanded, shared parking under future, neighboring development. A common driveway will enable the adjacent parcel to fully develop its street frontage on both Northwest 56th and Northwest 57th Streets. This response to the community’s desire for pedestrian-friendly streets in the new civic center allows for greater building density and fewer curb cuts.

Collective Wisdom & Feedback Loops

This project was a collaborative effort between ambitious owners, users, designers, and consultants. The partnership included an informed client and an active, interested public. This combination allowed us to push the limits of green design as a fully integrated series of systems and techniques. The public, informed of the design through a series of public meetings, was able to respond with feedback during and after those sessions. As a result, the public feels greater ownership in the facility. It is truly a community’s building.

The facility’s use provides a perfect opportunity to further educate the community in the benefits and availability of green design. Green design is often seen as adding insurmountable costs to a project. Through the careful integration of building systems and components, and by creatively looking for a multiplicity of functions in all of the systems and components, the Ballard Branch Library and Neighborhood Service Center has proven that a tight budget need not preclude responsible and responsive design.

Other Information

Highly visible special opportunities, such as a periscope and an observation deck, not only leveraged the educational value and emotional impact of green design, but also provided numerous naming opportunities for fundraising.

One innovative financing strategy was developed when a bank that was originally part of the project pulled out during the design development phase. The loss of that portion of funding caused the design team to consider replacing below-ground parking with surface parking in order to reduce costs. Instead, the team identified an option that created a dense building on the western edge of the site, allowing a 60-foot-wide parcel to be sold for mixed-use development. The funds from the sale of this property would be earmarked to pay for below-grade parking. The portion of the site was maintained as layout space during construction while being marketed for sale. The sale was delayed until construction was complete to maximize the sale price. Knockouts in the east wall of the structured parking further leveraged the neighboring property’s value by allowing an option to share a common drive, permitting a full 60 feet of storefront space on both faces of the through lot. The eventual sale netted $1,500,000, exceeding the cost of structured parking ($1,044,702), and provided a denser, more pedestrian-friendly neighborhood.

Cost Data

Cost data in U.S. dollars as of date of completion.

-Total project cost (land excluded): $6,500,000

Early, detailed cost estimating was paramount to the integration of sustainable design concepts ranging from the practical to the spectacular. One example of the practical is the innovative structure for the project. The cost of cast-in-place concrete with spray-on insulation from below and the cost of a floating slab over rigid insulation and precast planks proved to be surprisingly similar. The added benefits of eliminating both heat sinks and possible air-quality problems, reducing vibration and noise, and minimizing penetrations between the garage and the occupied space made this a simple choice. The clean separation between the structure and interior conditioned space also minimized the volume that had to be conditioned. While the dramatic effects of this system will not be perceived by the general public, the benefit of clean, exposed surfaces and a comfortable interior environment will be enjoyed by all.

The construction process was successful largely thanks to the dedication of the team, including the contractor and subcontractors. Scheduling an international product is always challenging, and this was no exception. A great amount of coordination was required to determine how to obtain properly sized units, whether to manufacture the them in Germany or the U.S., how to run the wires without compromising the structure or weather protection of the curtainwall, and how to wire the panels to get accurate meter readings at the sills.

The shipment was delayed several times, and the contractor chose to install temporary glazing to allow efficient conditioning of the space during construction. The architects diagrammed the wiring and routing through the window system after shop drawings were completed. Several team meetings refined the details for wiring and penetrations to assure a properly operating system. Calls to Schott in Germany and in the U.S. and personal contacts from all sides were required to optimize the system's performance.

Commissioning the solar installation resulted in several modifications. The inverters were oversized, which interfered with some of the readings and operation. The supplier replaced these with properly sized units. Also, individual meters were not registering due to incompatibility with the inverter hookup; this was corrected during replacement.

Individual meters in the sills were recommended to be ten amperes, although panel output was expected to be around three amperes. While the meters work properly, the minimal movement of the needles leaves some observers with the impression that the panels are not producing much power. The meters are being replaced with three-ampere meters, which will appear “pegged out” in full sun, making a far more powerful impression on observers. The greater variance in needle positions also makes it easier to see differences between the energy output of panels in full sun and in partial sun.

Additional Images

Project Team and Contact Information

| Role on Team | First Name | Last Name | Company | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architect (Senior associate and project manager) | Robert | Miller | Bohlin Cywinski Jackson | Seattle, WA |

| Architect (Associate and project architect) | David | Cinamon | Bohlin Cywinski Jackson | Seattle, WA |

| Owner/developer (Project manager) | David | Kunselman | Seattle Public Library | Seattle, WA |

| Contractor | Andy | McChord | PCL Construction Services, Inc. | Bellevue, WA |

| Structural engineer | Jim | Harris | PCS Structural Solutions | Seattle, WA |

| Civil engineer | Mike | DeLilla | RoseWater Engineering, Inc. | Seattle, WA |

| Mechanical, electrical, and plumbing engineer | Terry | Christian | Affiliated Engineers, Inc. | Seattle, WA |

| Landscape architect | Barbara | Swift | Swift & Company Landscape Architects | Seattle, WA |

| Acoustical engineer | Julie | Wiebusch | The Greenbusch Group, Inc. | Seattle, WA |

| Lighting designer | Mary Claire | Frazier | Candela | Seattle, WA |

| Cost estimator | Dan | Cassady | The Robinson Company | Seattle, WA |

| Artist | Donald | Fels | Fall City, WA | |

| Artist | Andrew | Schloss, Ph.D. | ||

| Artist | Dale | Stammen |